Dwindling stocks of Australian sperm have fertility clinics looking overseas and couples looking online

In 2010, Alice and her partner, Natalie, found themselves at a Sydney fertility clinic ready to start their family. Alice had recently completed her master’s degree and was in her early thirties, approaching an age where women are encouraged to panic about their fertility.

While undergoing pre-fertility testing the couple was provided with access to an American databank of donors. They homed in on a Chilean donor. “We had a bit of a connection with his bio, which sounds ridiculous,” Alice (not her real name) says.

During their next visit to the clinic, they were told that only a fifth of the database was available to Australian recipients. That number would be further curtailed by what would be available on the day of the procedure – frozen sperm has to be thawed and prepped for use. The day before Alice’s intrauterine insemination (IUI) she was told to choose her top three donors from a list of 12. When it was time to conceive, Alice was inseminated with her second choice. Now, as the mother of two children, this seems trivial but at the time it was “really hard”.

Many imagine choosing a sperm donor as a flick through a thick catalogue of multiracial, square-jawed men with medical degrees – a United Colors of Benetton campaign with sperm motility counts. But in Australia the supply entering fertility clinics has slowed to a dribble. Superficially, this is because Australia requires more from its donors than other countries: before his proverbial 15 minutes in a back room with a Styrofoam cup, a donor has to agree that offspring produced from his bequest are able to identify him once they reach adulthood. He has to perform the labour for free, although he will be reimbursed for “reasonable expenses”. He also has to sit through a counselling session to ensure that he understands the repercussions of his deposits: the email, door knock or phone call that could come in future. Once a donor is recruited, his sperm is only allowed to produce children in a maximum of 10 families, depending on the clinic’s state or territory.

Monash IVF has a three-month waitlist for women wanting to use artificial insemination. IVF Australia’s waitlist is also “a few months”, according to its medical director, Peter Illingworth. An interim review of assisted reproductive treatment in Victoria, led by lawyer Michael Gorton, has called for the establishment of a public egg and sperm bank to address the widespread donor shortage. Adnan Catakovic, the co-founder and scientific and managing director of City Fertility, which operates Sperm Donors Australia, Egg Donors Australia, Rainbow Fertility and First Step Fertility, says that there are 16 Australian donors available in New South Wales and 57 in Victoria. “If you are purely relying on [sperm from] Australian donors, there are clinics that have none,” Catakovic says.

One simple reason for this is that demand has outstripped supply.

At least some of the increased demand can be explained by legislative changes catching up with social acceptance of different family models. In 2008, the Victorian government passed the Assisted Reproductive Treatment Act, which ensured that lesbians and single mothers were given access to fertility clinics. Gareth Weston, a fertility specialist from Monash IVF, estimates that requests for sperm surged by a factor of four or five as a direct result of the legislation. Today the vast majority of patients requiring donor sperm are single women or same-sex couples.

On the supply side, in the 1980s the Victorian government was one of the first jurisdictions in the world to query the ethical implications of what had been a secretive and taboo process – with parents advised to erase the experience once the child was born – moving the legislative lever away from the rights of the sperm or egg donor towards the rights of the child. The Infertility (Medical Procedures) Act 1984, came into effect in 1988. Donor-conceived children born after 1988 were granted access to the identity of their donor – if their donor consented. From 1998, when the Infertility Treatment Act 1995 came into effect, those wishing to donate were no longer allowed to be faceless. Children born to sperm or egg donors after 1998 could access their donor’s details once they turned 18.

Donor-conceived children born outside of Victoria gained similar rights in 2005 when the National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines banned anonymous donation nationally.

In 2012, the Victorian parliamentary law reform committee completed an “Inquiry into Access by Donor-Conceived People to Information about Donors”. The most compelling case against anonymity was made by Narelle Grech, a donor-conceived, terminally ill woman desperate to meet her biological father. She was born in 1982 and was more than a decade into her search when she was diagnosed with stage-IV bowel cancer. Her disease was hereditary and did not exist on her maternal side. She was aware of eight half-siblings, whom she wanted to direct towards early screening programs. Victoria’s then premier Ted Baillieu intervened on her behalf and Grech met her biological father six weeks prior to her death.

As a result, in March 2017 Victoria changed its laws retroactively, such that every donor-conceived child in the state could identify their donor regardless of what the donor had consented to at the time. Once the child turns 18 – or younger if they are deemed mature enough by a counsellor – they are entitled to the identity of their donor. Contact is also permissible, with the donor’s consent. All of the fertility experts interviewed believe that budding donors were deterred by the frequently shifting legislation, concerned that the law that exists now may not apply to them in the future.

Professor Fiona Kelly of the La Trobe University Law School proposes another factor that may be contributing to the shortage of sperm donors. She believes that rather than being the result of Australian men becoming opposed to donating, it’s that clinics are choosing to import sperm instead.

“When you talk to some clinic staff who have gone down the importation route you can see it becomes very easy for them to just import,” she says.

Most of the international sperm entering Australia is from the US and Denmark. There is a risk we could be importing some of the headlines seen in the US, where issues pertaining to sperm donors are a standard ingredient of both long-form think pieces and clickbait. Recent examples include: “A Fertility Doctor Used his Sperm on Unwitting Women”, “Fertility Doctor Sued for Using Wrong Sperm” and “Children with Gene Disorder Share Sperm Donor Dad”. Kelly is also concerned that engaging with the US market could dilute the strength of Australia’s hard-won laws.

While in Australia the commercial trade of gametes – sperm and eggs – is illegal, in the US gamete production is a mercantile endeavour. Online news site Vox recently ran an account of Californian man John Carpantier, who signed a 12-month contract with a clinic and made US$12,000 from his bi-weekly deposits.

Nevertheless all international sperm banks are supposed to meet Australia’s stringent legislative requirements if they plan to export gametes to our fertility clinics. This includes identification disclosure and counselling by a practitioner approved by the Australian and New Zealand Infertility Counsellors Association. Donation must also be unpaid. In the US, this would require a donor to a sperm bank to forgo payment, even though it’s on offer – a scenario that seems far-fetched.

I query this with Adnan Catakovic, who maintains that there is a cohort of American donors who are sufficiently altruistic. California Cryobank, for example, only accepts sperm donation from college students or graduates. “So, a lot of the donors are quite intelligent, affluent – lawyers, accountants, engineers,” he says. “They don’t need the money.”

Fiona Kelly is sceptical of trusting the larger American sperm banks, whose main benefactors are students. “All of their donors are usually paid and the idea that there are wealthy donors acting altruistically… there is very little evidence of that.”

When exporting to Australian clinics, American sperm banks must guarantee that when a child reaches adulthood they will release the donor’s identity. Australian laws regulate the process, but a child born from an American sperm bank is relying on that institution to update the donor’s address and contact details for an 18-year minimum (and children can be conceived years after a donation is made). Kelly is concerned that donor-conceived children will be born into a two-tier system, with access to information hinging on the nationality of their DNA.

In some ways access to identifying information is becoming a moot point. Mail-order DNA-testing kits – from websites such as 23andMe – and social media make it much easier for donor-conceived children to find genetic relations. Then there is the US-based Donor Sibling Registry, the closest thing that the artificial-¬reproduction industry has to a global database. The website was started in 2000 by Wendy Kramer, to help her son trace information on his genetic origins, and it grew into a consensual outlet for donor-conceived individuals to locate their biological parents and half-siblings. Today the site has almost 65,000 members, more than 17,000 of whom have been reunited with their genetic families. There are 1200 Australian families on the site.

The registry also reveals how apathetic American sperm banks are in regulating family limits – the number of related offspring permissible. Kramer identified a donor with more than 200 offspring, and is aware of a dozen donors with more than 100 children (some of whom were conceived in Australian clinics). There is evidence of sperm from the US being shipped to two clinics in Queensland and NSW that both believed they had sole access to the donor’s gametes.

The only whiff of family-limit regulation in the US is a discretionary recommendation by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), which suggests clinics restrict births from one donor to 25 per population of 800,000. In any case, the ASRM is an industry body, not a legislative one. Kramer says it’s a case of the fox guarding the henhouse.

The maths doesn’t translate well either. If applied to Australia, that donor would be able to sire 768 children.

The laws surrounding artificial reproduction in Australia are abundant. Sperm donors are recorded and regulated by a tangle of acts and acronyms that differ between states. In brief, New South Wales, Western Australia and Victoria and have central registers, which clinics must notify and provide with updates. Other states are regulated by the Reproductive Technology Accreditation Committee (Fertility Society of Australia), with clinics maintaining donor information and passing it on to the offspring once they turn 18. These regulations also include different state and territory fixed–family limits, expressed as a permitted number of recipients rather than offspring: five women in NSW, 10 women in Victoria, five families in WA, and 10 families elsewhere around the country.

Catakovic believes family limits on donors are arbitrary. “I always get a little bit of frustrated when something applies to a subset of infertile couples that doesn’t apply to the general population,” he says, citing data which showed the probability of two children, born to the same donor, meeting and having a relationship as “infinitesimally small”.

Nonetheless, crossing paths with someone who shares half of your DNA is not as far-fetched when considering the possibility of communities with potentially high rates of reproductive assistance. There are, for example, clusters of “rainbow suburbs” with sizeable LGBTI populations. “They all send their children to the same schools – often intentionally,” Kelly says.

In April, Daily Mail Australia reported on a Brisbane couple who stumbled upon the discovery that a neighbour used the same donor as them. The donor’s sperm came from Queensland Fertility Group and was responsible for the creation of 48 children. According to the Donor Sibling Registry, his sperm was in use as early as 2003, predating family-limit guidelines.

On top of all this knotty complexity, the wording of some of these laws has turned out to discriminate against same-sex couples: in the states where donor limits apply to women rather than families, partnered lesbians are counted as two separate entities rather than a family unit.

Alice and Natalie experienced this pitfall when they were ready to conceive a sibling for their firstborn. Natalie had planned to carry the next pregnancy by being inseminated with sperm from the same donor as Alice, so that both women would have a genetic link to their offspring. In the interceding years their donor had reached the five-woman limit in NSW, classifying Natalie as a sixth woman, even though she already had a daughter conceived from his sperm. Alice was given an option to circumvent the regulations by carrying an embryo fused from the donor’s sperm and Natalie’s egg making her the surrogate mother of their second child. But this method failed, and Alice’s eggs were used for both of their children.

Reproductive technology comes with a hefty price tag. Alice jokes that her oldest child cost her $5000 while her youngest cost $30,000.

Cost is also another piece of discrimination built into the regulatory framework, with Medicare only reimbursing those who receive assistance for clinical, not social, infertility.

“It’s terrible discrimination, but we get very little sympathy from the federal government,” Monash IVF’s Gareth Weston says.

Without a rebate, Monash IVF charges $2268 for IUI. This does not include the cost of accessing the sperm bank, which Weston says costs around $750 each round. American donor sperm is even more expensive, of course, due to shipping fees. Success for IUI is low: for women under the age of 35 the average rate is 20 per cent, and many move on to far more expensive IVF procedures to conceive.

Complying with sperm-donor guidelines is also expensive, and the cost is inevitably landed on the recipients. Weston explains that donors have to go through 20 clinical contact points before their sperm is released for use. This includes semen analysis, blood tests, psychological counselling, genetic counselling and genetic testing. The sperm is then quarantined for a minimum of three months to ensure that no diseases have emerged in that period. Without the compensation of a payment, it’s easy to see why supply has decreased.

Fertility clinics project the notion that their services are vital to at least one step of the conception process. But many Australian women see their services as unnecessary frills, like a restaurant charging thousands for a product that is free and simple to prepare at home.

Little wonder, then, that Australia has a robust peer-to-peer economy of sperm.

In March 2019, Julia and Maria – not their real names – attended the mandatory counselling sessions in a Sydney fertility clinic. Julia believed the first session, which outlined their legal position, was worth its $250 price tag. “The second [session] was ridiculous,” she says. “[The counsellor] had nothing to say to us.”

Julia and Maria married in January 2018 with only vague notions of how they would start a family. They have been living in Sydney since the beginning of this year, in a small and neat unit in the eastern suburbs. The wall next to their dining table is decorated with three analogue clocks, one displaying the time in Sydney, while the other two show the time in Berlin and Campo Grande, Brazil, their respective hometowns.

Following the counselling sessions, Maria, who planned to carry the first pregnancy, was declared to be sufficiently fertile. However, she was recommended to take a drug that would stimulate her ovaries. The suggestion made her uncomfortable and the chance of becoming pregnant was still just 20 per cent. Moreover, when it came to the process of choosing their donor, options were limited. There were three choices of donor sperm at the clinic and two of them were Asian. Julia didn’t want to add an extra ethnicity to the child’s already complicated heritage. Ultimately they decided to look online, in particular on a gamete-matching website called Coparents.

Finding sperm online is astonishingly simple. There are multiple websites matching donors to recipients, in stark contrast to the reports of dwindling stocks in clinics. Coparents had 978 sperm donors available in Australia at the time of writing, and similar site Co-ParentMatch had 1123. Donors display photos and list their hobbies, interests, religion and other data that they believe may be relevant, and also state their conditions for engagement. A brief search on Co-ParentMatch presented, for instance, a 42-year-old man from Sydney who describes himself as an actor, model, artist and mechanical engineer with an IQ of 150. He also states that he is “able to provide, emotional support, Mathematical tuition, project building ie; Robots, Excercise [sic] training” to his biological offspring.

In 2017, Paul Ryan launched his app, Just a Baby, on the night of the Sydney Mardi Gras, in order to attract “an immediately interested audience”. It has a location-driven swiping interface that mirrors Tinder, and a cheery logo of a cartoon baby with a curly cowlick. Ryan is deliberate in defining his app as solely a meeting place for sperm or egg donors, surrogates or people interested in a co-parenting arrangement. Many then use clinics when their needs align. The app is designed to be part of “a healthy ecosystem” including fertility clinics and sperm banks that help socially infertile people. “I just think that maybe we’ve over complicated things,” he says, “and as a consequence, we’re now missing a degree of human connection.” He doesn’t keep track of how many lives have been created from the technology (anecdotally it’s “heaps”) or the processes of conception, some of which take place beyond the walls of a clinic.

In February, an American by the name of Joe Donor toured Australia, inseminating women both artificially (with a syringe) and the old-fashioned way. Prior to his arrival, he boasted of having more than 100 offspring. An episode of 60 Minutes commenced with footage of him driving in the dark of night accompanied by eerie music, and deemed him “a public health risk”. The ABC’s Media Watch later established that Channel Nine bankrolled his flight and was aware of his clean bill of health.

Joe Donor’s Facebook page revealed at least one Australian woman became pregnant as a result of his tour. He claims that the African-American women he inseminates have blue-eyed offspring and straight hair, and in a post linking to a YouTube video called “Get Your Swirl On” Donor writes: “The USA is a pigmentocracy where those with lighter skin color and more typical northern European features have more opportunities … You, too, can have a baby with the whitest possible features.”

These informal networks are not illegal, but, understandably, lawyers and fertility clinic staff have all cautioned about the health risks and legal implications of getting pregnant in this manner. The Donor Sibling Registry’s Wendy Kramer refers to Joe Donor and others who sell their services through social media as “Craigslist Donors”, and in Australia there are several groups using such platforms to make babies.

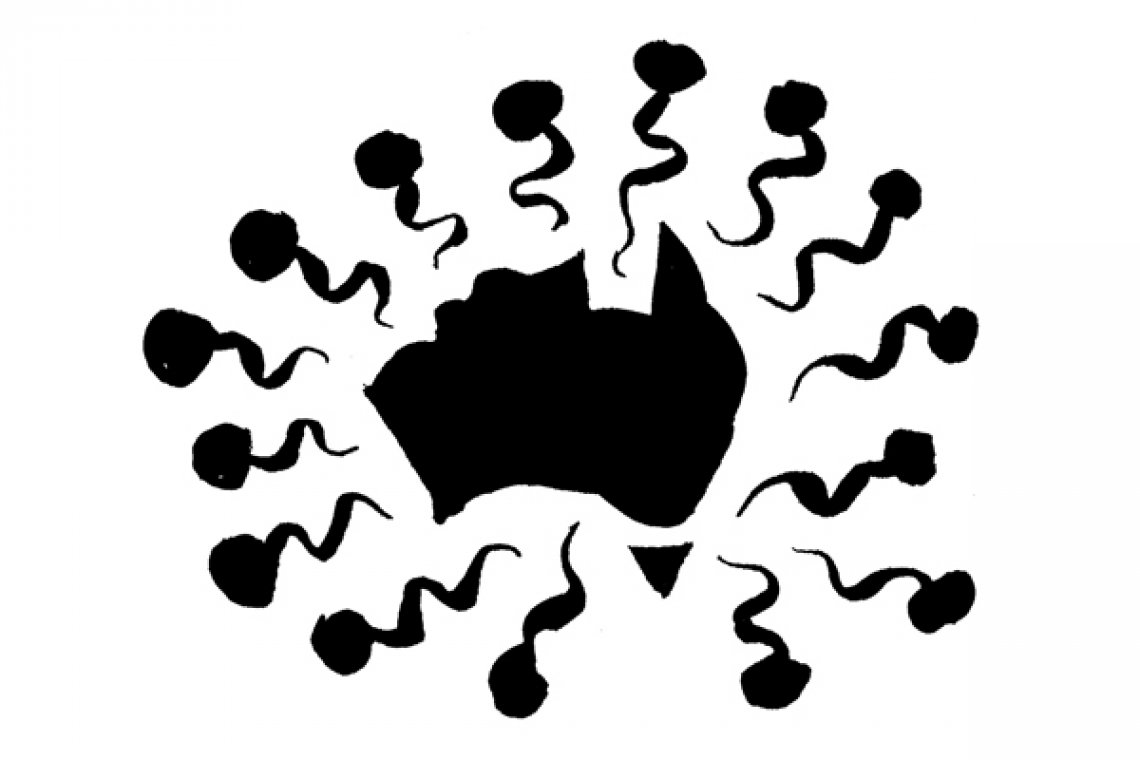

Sperm Donation Australia is a Facebook group run by Adam Hooper, a 34-year-old Western Australian FIFO worker. Its banner is an illustration of sperm encroaching towards a map of Australia, a graphic resembling a campaign against immigration – not that it’s repelled any of the group’s 5000 plus members. The group has reportedly led to hundreds of pregnancies but is not quite the black market for white fluid that one might anticipate. There is no sperm for sale. Mostly, members post with their prerequisites and those who are interested identify themselves in the comments. The process is bi-directional – one woman asked a potential donor for a close-up of his eye colour, to see if it matched the green of her partner’s. (Hooper, who has two children of his own, has himself informally donated to roughly 10 families but does not reveal the number of children he has produced in case it “creates a competitive culture”.)

The group also functions as a fertility forum with members exchanging information on the best way to conceive: comparing the efficacy of syringes to menstrual cups, advising each other on how long to lie down after insemination, whether an orgasm increases the chances of getting pregnant and if it’s better to release sperm from the syringe quickly or slowly. There are numerous posts of ultrasound images and baby pictures from women who are grateful to the platform for propelling them into motherhood.

Hooper asked men in the group why they prefer to offer their DNA in the social-media arena. One said he had already reached his family limit for donation to a sperm bank and another perceived the clinical environment as impersonal, but the vast majority of responders wanted to have a say in the direction of the genetic legacy. Which is understandable, considering the likelihood of their offspring’s name appearing in their inbox in 18 years’ time.

Kellie-Anne Farrawell and her female partner stalked Hooper’s Facebook group for a few months before posting an advertisement: “We have bought a house, settled down and are looking to start a family together. We both have fulltime jobs within government and currently raise 2 two year old dogs and 4 chickens.”

I meet Farrawell in a bakery in Appin, a town 75 kilometres south-west of Sydney. She is accompanied by her smiley five-month-old son, Zac, whose ears protrude from beneath a black baseball cap. She recalls how she combed through the responses and met with two potential candidates, settling on the donor that she and her partner “had a better feel with”. He told the couple that he did not appreciate how fortunate he was to have children until he witnessed his friends struggle with infertility. Farrawell didn’t ask why he chose not to pursue a clinic to make his donation. “From talking to him, he wanted to help the right people,” she says.

The women were aware that they did not have the genetic-testing resources or the quarantine capabilities of a fertility clinic to “rule out the nasties”, but they were methodical in their approach. They viewed the donor’s STD results, discussed his genetic history, established specifics such as how many women he intended to impregnate and how long he would assist them. (“If we didn’t conceive after six months he was out.”) They discussed whether he wanted photos, meetings or updates – he didn’t, but was happy for the child to be in touch once they reached adulthood.

The donor had his own concerns: he had a wife and two children and was worried about the women asking for child support.

Once the trio settled on specifics they signed a donor agreement. Lawyer Nicole Evans, author of Lesbians and the Law: A Guidebook for Australian Families, underlines the importance of such a document, which despite not being legally binding shows evidence of intent: “The court may put some weight onto it, if you enter a dispute.”

Farrawell tracked her fertility cycle and hired a motel room near the donor’s home when ovulation approached. They left the donor “to do his thing” and lingered in the pub downstairs. It was topless-waitress night. Eventually the nervous couple received a thumbs-up on Facebook messenger. When they returned to their room the donor was gone, but his donation ready for use. Farrawell employed a 10-millilitre syringe and became pregnant at first attempt.

Before attending a fertility clinic, Julia and Maria had found a donor from a different Facebook group. “I think he was a doctor and he worked at a university,” Maria says. They met him at a cafe after work, verified that he was disease-free and made the appropriate inquiries. “He seemed very confident and dictated the process to us,” she says, adding that he told her he had produced at least 50 children.

They booked a two-night stay in a motel to coincide with Maria’s fertility window. The first night the donor showed up he complained that the vessel the couple had supplied for him – a menstrual cup – was too small. As a solution he proposed that he would bring himself close to ejaculating and have brief intercourse with Maria, which the two women immediately rejected. Instead, they searched for a late-night chemist and bought a suitably sized receptacle: a urine-sample jar with a bright yellow lid. Maria inseminated herself with the deposit after the donor left. The second night, he arrived at the hotel with the top buttons of his shirt undone. When he began to remove his shorts Julia and Maria asked him to leave, which he did. Maria did not become pregnant.

Julia was unnerved by the incident – “he was super confident and strong” – and was concerned that single women accepting his sperm may be vulnerable. But she chose not to report the event to the Facebook group’s administrators. “I don’t know,” she says, “maybe people will think he’s attractive and want to have sex with him.”

The incident scared the couple into using a clinic. Their first counselling session – the one they deemed worth their money – informed the women that if sex took place their donor would have been the legal father of their child and may have been granted parental rights.

On Hooper’s Facebook page, sex is referred to as “natural insemination” or “NI”. Initially, he wanted to ban the practice from his group. “There are doctors telling women that the best chance of getting pregnant is by doing that,” he says. “Ultimately it’s up to them.” Donors and recipients are instead required to list their preference when they advertise.

Even when done through a clinic, sperm donorship can upheave a family dynamic. The last decade’s legislative changes have moved to demystify a donor’s identity, establishing statutory bodies that assist the linkage of parents with their sperm donor, even before the child turns 18. La Trobe University’s Fiona Kelly has witnessed a rise in parent-initiated contact and says there is limited discussion about what these connections mean in the context of family law.

In a landmark case in June, the High Court ruled that a sperm donor was his daughter’s legal father, and had the right to prevent her mothers from relocating to New Zealand. The donor was known to the family, and the decision seemed obvious: his name was on the birth certificate, he financially supported the child, and the daughter called him Daddy.

But most known donors fall into a grey area. Some take their children on regular trips to the zoo, others send a birthday card by mail. Kelly is concerned that the judgement is dichotomous, declaring the donor as a parent without elaborating on the steps taken in establishing parental status. There’s no clear legal juncture where the friendly-uncle-figure morphs into a father.

Kelly advises women who are considering making contact with their donor to “hold off” and warns those who have already started a dialogue to proceed with caution. “His legal status is up in the air right now.”

After the High Court decision I contacted Julia. She disclosed that Maria was already pregnant by a donor from the Coparent website – a gay Buddhist from Italy.

Even despite her earlier ordeal, she insisted that they felt comfortable with him and saw no need for a donor agreement form. “My mindset’s already moved on from the topic now,” she says. “It’s all about pregnancy.”